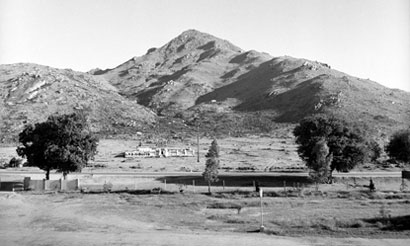

The sacred Arunachala Hill rises alone from the surrounding plains to a height of 860m. Geologically, the hill is an outlier of the Easter Ghats, a broken line of ancient granitic hills that run the length of the India’s eastern side, and passes less than 30km to the west of Thiruvannamalai. Older, drier, and lower than the Western Ghats, the different ranges of the Eastern support a variety of forest types, home to innumerable plant and animal species.

Arunachala too would once have been covered in such forests, and ancient Tamil poems attest to as much. But years of wood-cutting and man-made fires left only pockets of stunted trees on a rocky hill covered predominantly in a single species of grass.

The Forest Way grew out of work begun in 2003 to address this situation. Even earlier efforts by both the Forest Department and other local groups had shown that it was possible to grow trees once more on the Hill, but without dealing with the annual fires, the benefit of these efforts was always localized.

Our aim is not simply a return of tree cover to the Hill, but a broader restoration of its complex ecosystems. We know that life desperately wants of live. Nature has an immense power to heal itself if only given the chance. The best use of resources is usually to simply protect and allow the forest to return. At the same time, we strongly feel that people can have an active and positive part to play in helping the forests return. When people do this, it not only helps the forest, but gives great value to the lives of those who partake in this wonderful process.

So our work encompasses active prevention of fire on the hill, raising and planting out trees and other plants, protection, education, community action, continual observation and artistic enjoyment. We aim to let nature dictate our actions, and to let natural feedbacks prove or disprove those actions.

Successful prevention of fire has taken place through co-operation with the Forest Department and young volunteers. The result has been that forests are returning rapidly across the entire hill. Increases in bird and animal life further affirm that positive change is underway. Tree planting augments and speeds up this process, and bringing local schoolchildren to this young forest and allowing them to form a bond with it lays down further connections that will protect the trees in years to come.

Our Nursery

Setting up a high quality nursery of native forest plants was one of the first things we did when starting out, and it remains the very heart of our greening work.

Each year we raise tens of thousands of saplings, from over 100 indigenous species. Many of these plants go directly to the slopes of Arunachala, but we also give free trees to any local schools that request them. The local Forest Department value the quality and diversity of the plants, and are regular visitors to the nursery, as are various local NGO’s and private gardeners. One of the functions of the nursery is to give native plants back their rightful place in home gardens, where they can bring in wildlife and reduce water usage. Medicinal plants are also raised, which can be planted in a kitchen garden and used for a variety of common ailments.

Each year we raise tens of thousands of saplings, from over 100 indigenous species. Many of these plants go directly to the slopes of Arunachala, but we also give free trees to any local schools that request them. The local Forest Department value the quality and diversity of the plants, and are regular visitors to the nursery, as are various local NGO’s and private gardeners. One of the functions of the nursery is to give native plants back their rightful place in home gardens, where they can bring in wildlife and reduce water usage. Medicinal plants are also raised, which can be planted in a kitchen garden and used for a variety of common ailments.

The work of the nursery team includes seed collection, preparation and germination of the seeds, and care for the young plants until they are ready for planting.

The work of the nursery team includes seed collection, preparation and germination of the seeds, and care for the young plants until they are ready for planting.

Collecting our own seeds increases our understanding of the favored conditions of a species, and our feeling for the forests that we are trying to re-grow. Learning how to germinate the many different species, watching the different ways they grow, it all serves to deepen our understanding of and empathy with the plants, and ensures that we plant out healthy young trees, grown with care and without toxic chemicals.

Tree Planting

Each year, with the monsoon rains, we plant around 15,000 young trees on the slopes of Arunachala, from a selection of more than 70 indigenous species. The work progresses in two phases. First, as stoon as there is enough rain to soften the the ground, we begin pitting. The men work in pairs; using a crowbar, one of them loosens the soil and levers out the many stones, while his partner to scoops these out with the mattock. The pit must be at least 45 cm deep, to give the roots enough loose soil to grow into. It’s hard work in the rocky terrain and there may be up to an hours climb to the planting area. Each pair of men is able to dig around 50 pits in a day.

Each year, with the monsoon rains, we plant around 15,000 young trees on the slopes of Arunachala, from a selection of more than 70 indigenous species. The work progresses in two phases. First, as stoon as there is enough rain to soften the the ground, we begin pitting. The men work in pairs; using a crowbar, one of them loosens the soil and levers out the many stones, while his partner to scoops these out with the mattock. The pit must be at least 45 cm deep, to give the roots enough loose soil to grow into. It’s hard work in the rocky terrain and there may be up to an hours climb to the planting area. Each pair of men is able to dig around 50 pits in a day.

Planting time is a real frenzy of activity. Up to a hundred people are involved in the rush to get the trees into the ground as early as possible. There is no chance to water the trees through the summer months, so early planting gives them the best chance to establish well, and then to survive the long summer. After planting, mulching the ground around the young sapling increases it’s chances further, as does creating a small catchment bund to collect precious summer rains. Attention to soil quality, to aspect, altitude and exposure is also important when selecting species for any given location.

Planting time is a real frenzy of activity. Up to a hundred people are involved in the rush to get the trees into the ground as early as possible. There is no chance to water the trees through the summer months, so early planting gives them the best chance to establish well, and then to survive the long summer. After planting, mulching the ground around the young sapling increases it’s chances further, as does creating a small catchment bund to collect precious summer rains. Attention to soil quality, to aspect, altitude and exposure is also important when selecting species for any given location.

In addition to our work on the hill, over the years we have planted trees in various different situations in and around Thiruvannamalai. These include roadside planting, the campuses of local schools and colleges, private farmland, and on village, municipal and temple lands.

In addition to our work on the hill, over the years we have planted trees in various different situations in and around Thiruvannamalai. These include roadside planting, the campuses of local schools and colleges, private farmland, and on village, municipal and temple lands.

On the slopes of the hill, the survival rate of the trees varies greatly due to a number of factors. Probably the most crucial of these is the timing of summer thunderstorms, and the arrival of the south-west monsoon. If there is no rain in July/August, the incessant dry winds that are a feature of that season can be more damaging to the plants than the heat of April and May. However, after 2 years the survival averages around 50%, which we feel is extremely positive.

Background to the Fire Problem

Though reforestation efforts began back in the nineteen eighties, the main impediment to regeneration on the hill was the frequent fires, which remained unchecked.

It seems that setting fire on the Hill was a deliberate practice dating back many decades, to promote the dominance of a type of wild lemon-grass (Cymbopogon martini), used locally as thatching for houses. On the deciduous slopes of forested hills in the region, this grass can be found, but it grows small and does not dominate. Out in the open however, the grass thrives and grows up to 2m tall. Due to it’s oil content it burns extremely easily, and with the following rain happily comes back from the roots.

After cutting the grass, the grass-cutters would burn off the stubble. This made the grass easier to cut the following year, and also killed off other plants that might shade out the grass. Although the grass cutters would not have harvested the entire hill, the fires would spread to burn all areas, resulting over time in the dominance of the grass over the entire hill.

In more recent years however, the demand for thatch has dramatically reduced as people switch to concrete roofs. These days there is minimal grass cutting, and the grass cutters do not set fires. However, the legacy of years of fire remains, in the predominance the highly flammable lemon-grass. Whether they are started by carelessness or intentionally, we still face the threat of fire each year.

Four Core Elements of Our Fire Strategy

Education

Over the years we have held a number of meetings with the communities living at the base of the hill. The main access to the slopes of the hill is above the town, and it is on this slope that nearly all the fires start. This is also the only area of the hill where people actually live on the slopes. These meetings have gone beyond just raising awareness of negative affects of fire; they have resulted in an amazing team of young fire-fighting volunteers. These boys are often the first on the scene when a fire starts, and over the years some of them have become veterans at beating out the flames. In gratitude and recognition of their work, we’ve had fire-fighter shirts printed for them, and presented them with sports equipment. But these tokens pale in comparison to the pride and camaraderie we all share when a fire is put out.

Over the years we have held a number of meetings with the communities living at the base of the hill. The main access to the slopes of the hill is above the town, and it is on this slope that nearly all the fires start. This is also the only area of the hill where people actually live on the slopes. These meetings have gone beyond just raising awareness of negative affects of fire; they have resulted in an amazing team of young fire-fighting volunteers. These boys are often the first on the scene when a fire starts, and over the years some of them have become veterans at beating out the flames. In gratitude and recognition of their work, we’ve had fire-fighter shirts printed for them, and presented them with sports equipment. But these tokens pale in comparison to the pride and camaraderie we all share when a fire is put out.

Prevention and Early Detection

For the length of the dry season, we employ five people as full time fire watchers. Strategically positioned, their job is to inform people climbing the hill of the fire risks, and check is they are carrying matches or lighters. Their other function is as an early warning for when fire does manage to start. This is crucial, as the longer it takes for us to get to the fire, the harder it will be to put out.

Fire Lines

Each year we create around 14km of fire breaks across the slopes of Arunachala. This involves the complete removal of all ground vegetation across a strip 10m wide. This is a huge annual undertaking, but has been an absolutely crucial part of our success in controlling fire.

A freshly cleared Fire Line

Fire Stopped; with a Fire Line 10m wide, a ground fire almost never crosses.

When Fire Starts, Put it Out.

The final part of the strategy is of course to physically fight any fires that do occur. Our methods are simple but effective; using branches with green leaves, we beat the flames down. We have found this more effective than purpose made rubber beaters, and more advanced technology such as fire extinguishers would be too expensive. It’s exhausting work in intense heat. It can be difficult to see and breathe due to the smoke. The fire fighters wear only simple sandals on the steep rocky ground. Getting enough drinking water to the site of the fire is crucial but often difficult. And yet despite all this, time and time again this amazing team succeeds in extinguishing the fire.

The results: How the Forest responds

While tree planting has been a great success, and it gives us immense pleasure to see the young sapling growing steadily, all these efforts are dwarfed the natural re-growth across the entire Hill in the years since the fire has been stopped. We are reminded how efficiently and dramatically nature will recover if only given the chance.

Forest Park

The Forest Park is the focal point for our greening work. It is here that our restoration efforts have been most intensive and where the results are most visible. Here also is the nursery, and from the park, during rainy season, we spread out to the slopes of the Hill to carry out the planting work. Crucially, the Forest Park is a place where local people, especially children, can meet and begin to know the forests of the region.

The park covers around 15 acres at the foot of the Hill. This transition from the plains to the lower slopes is potentially a very rich habitat. Different species of birds and mammals use the shelter of the rocks and scrub of the lower slopes, then spread out to feed in the mosaic of farmland, scrub jungle and patches of thicker forest found on the flats. The ancient tanks and recently dug ponds provide year-round water, and the deeper soils and higher water table allow for a different type of forest to that found on the slopes. This habitat is also under great stress, as privately held land at the foot of the Hill gets converted from crops to building plots, squeezing the remaining wildlife and blocking passage to forest areas beyond the Hill. In this context the park, while small, provides a vital patch of edge habitat and is the last such patch of flat ground before the town begins. This habitat is further enriched by the presence of one of the major seasonal streams that flow from the hill. Depending on rainfall patterns, this stream flows for up to 6 months a year. Here we are able to restore a small ribbon of riparian forest, with its very distinctive and beautiful species makeup.

The park covers around 15 acres at the foot of the Hill. This transition from the plains to the lower slopes is potentially a very rich habitat. Different species of birds and mammals use the shelter of the rocks and scrub of the lower slopes, then spread out to feed in the mosaic of farmland, scrub jungle and patches of thicker forest found on the flats. The ancient tanks and recently dug ponds provide year-round water, and the deeper soils and higher water table allow for a different type of forest to that found on the slopes. This habitat is also under great stress, as privately held land at the foot of the Hill gets converted from crops to building plots, squeezing the remaining wildlife and blocking passage to forest areas beyond the Hill. In this context the park, while small, provides a vital patch of edge habitat and is the last such patch of flat ground before the town begins. This habitat is further enriched by the presence of one of the major seasonal streams that flow from the hill. Depending on rainfall patterns, this stream flows for up to 6 months a year. Here we are able to restore a small ribbon of riparian forest, with its very distinctive and beautiful species makeup.

Our work on the slopes of the hill is extensive in nature, planting and protecting large areas and then letting nature take it’s course. In the park however we are able to work more intensively, using gardening skills to help the forest back to health. We are also working with a view to creating maximum diversity of the plants native to the region within this relatively small area. Partly this is for it’s own sake; diversity needs no justification. But it is also so that we can begin to understand for ourselves as much about the local plants and their needs as possible, so that we may put that understanding into wider use. And finally it is give visitors to the park the opportunity to meet as wide a range of the local flora as possible, that they may begin to know the richness of the region’s forests.

Our work on the slopes of the hill is extensive in nature, planting and protecting large areas and then letting nature take it’s course. In the park however we are able to work more intensively, using gardening skills to help the forest back to health. We are also working with a view to creating maximum diversity of the plants native to the region within this relatively small area. Partly this is for it’s own sake; diversity needs no justification. But it is also so that we can begin to understand for ourselves as much about the local plants and their needs as possible, so that we may put that understanding into wider use. And finally it is give visitors to the park the opportunity to meet as wide a range of the local flora as possible, that they may begin to know the richness of the region’s forests.

For this is a major function of the Forest Park; to facilitate meeting between the people of the area and the other life forms whose home this place is too. A few well laid out paths allow people to wander without disturbing the plants, benches by the ponds allow them to sit quietly and observe. Knowing that that not all of the wildlife may want to meet the visitors, local artist Kumar has been working for the last five years on an outdoor gallery of the wildlife of the hill and it’s surrounds. Painted on large slate stones, these works are wonderful way to familiarise oneself with animals of the hill. There are also information boards, giving opportunity for further understanding. We have also nearly completed work on a building that will become a small natural history museum for the region, and an interpretation centre for the flora and fauna of the area. This will really augment the already rich education programmes that happen in the park.

For this is a major function of the Forest Park; to facilitate meeting between the people of the area and the other life forms whose home this place is too. A few well laid out paths allow people to wander without disturbing the plants, benches by the ponds allow them to sit quietly and observe. Knowing that that not all of the wildlife may want to meet the visitors, local artist Kumar has been working for the last five years on an outdoor gallery of the wildlife of the hill and it’s surrounds. Painted on large slate stones, these works are wonderful way to familiarise oneself with animals of the hill. There are also information boards, giving opportunity for further understanding. We have also nearly completed work on a building that will become a small natural history museum for the region, and an interpretation centre for the flora and fauna of the area. This will really augment the already rich education programmes that happen in the park.

The Forest park is contiguous with the Children’s park and the Arboretum, making a substantial area of public land at the foot of the Hill that we have managed to protect for people and wildlife alike, from the all too powerful forces of ‘development’.

The Arboretum

The beautiful horse and cattle market in full swing

Adjacent to the Forest Park is a further 8 acres of government land that each year, during the Deepam festival, hosts a glorious cattle and horse market. This fair goes back centuries and remains a highlight of the Thiruvannamalai calendar. However, for the remainder of the year, the land is neglected and becomes an informal dumping ground and drinking spot. These bring with them a fire risk, and prevent the land being enjoyed by other people.

We had for some time dreamed of including the area in the forest park, regenerating the land, and safeguarding further buffer zone at the foot of the Hill. But any ecological regeneration of the area had to work around the cattle fair, which needed space, and would have destroyed any young trees before they could establish.

As the area is otherwise

The answer was to create an arboretum to showcase the trees native to the Hill. These would be planted with large spacings, making each one a specimen tree that could be enjoyed individually, at the same time allowing plenty space below for the cattle market to happen. In the nursery we began raising extra large samples of the various species in disused barrels, so that when planted out they would already have a head start on the cows. Then, in September 2010, a planting ceremony was held, attended by the District Collector, Local MLA and Town Chairman. This was a big step toward safeguarding the land for all.

At present there are forty trees planted out in the Arboretum. There is space for perhaps one hundred large trees, representing over half of the tree species of the area. We are busy collecting and growing the remaining specimens to be planted out over the next couple of years. Once planting is finished, and the trees reach a size where they no longer need individual protection, we will illustrate information boards for each tree, detailing medicinal and other uses, ecology of the tree, where it can be found, and any other points of interest. The area will then be opened up to the public.

District Collector and Thiruvannamalai MLA plant the first tree

Arboretum specimens growing nicely

Water conservation

Some of the earliest major works in the Forest Park and the Children’s park were the creation of a series of ponds that would be able to fill in the monsoon and thus recharge the groundwater, create further habitat for plant and animal life, and bring some added beauty into the parks. These ponds were dug almost entirely by hand. This meant working at a speed where the contours of the land and the rocks within could dictate the shapes of the ponds. The excavated silt and rocks came at a speed conducive to creative use in landscaping and gardening. Working by hand also meant spreading the cost of the ponds around many families for months, rather than one JCB owner and the petrol companies.

While the ponds are lovely to see full of water after the monsoon, the real water conservation connected to our work is largely unseen. Prior to 2003, annual fires burned the covering vegetation from the hill slopes. This exposed the soil to summer sun, baking it hard. When the rains arrived the water ran off the steep, hard slopes, carrying with it precious soils. Streams ran fast, full of sand and silt, and quickly dried up when the rain ceased.

While the ponds are lovely to see full of water after the monsoon, the real water conservation connected to our work is largely unseen. Prior to 2003, annual fires burned the covering vegetation from the hill slopes. This exposed the soil to summer sun, baking it hard. When the rains arrived the water ran off the steep, hard slopes, carrying with it precious soils. Streams ran fast, full of sand and silt, and quickly dried up when the rain ceased.

From 2004 onward, we noticed a dramatic change in this pattern. As each year the areas burned were reduced, so the streams took longer to begin flowing with the onset of the monsoon. The sediment they carried was dramatically less, and they flowed for longer after the rains stopped. On the slopes of the hill organic matter was being allowed to build up. This acts as a sponge to soak up the rain. Even in the absence of rain it protects the soil from the worst of the sun’s heat, keeping it softer and more permeable. Soft soil with organic matter encourages more and more soil organisms. Their burrowing and turning of the soil makes it more permeable still, so that the water infiltrates deeply. This in turn encourages better plant growth, producing more organic matter, which absorbs more water, and on it goes. Humans aside, life almost always generates the conditions to further life.

The stream that flows through the park is the one that we have watched most closely. In 2004 we constructed a small check dam in the stream. With the the first big rain, the stream rushed down and the pond above the dam filled completely with sand. We emptied out and used this sand. With the next big rain, the process was repeated, and so on, at least four times through the course of the monsoon. The next year there was far less sand, and from the year following that, until now, almost none. It takes the stream at least 2 weeks of good rain to start flowing, and after the rains stop it continues to flow for more than a month.

Preventing the fires that used to burn off the vegetation each summer has meant that the soils on the slopes of the hill are protected from the rain. Organic matter is allowed to build up. This acts as a sponge to soak up water and hold it in the soil. At the same time, soil organisms that feed on the organic matter multiply, and their actions lighten the soil, allowing the water to infiltrate deeply. More porous soil, with organic matter, holding more water for longer, promotes better growth in the plants. Their roots lighten the soil more, whilst holding it together and protecting it further. Life supports life.

In the early years of the project the changes that these processes caused in the flow pattern of the seasonal stream that runs through the park were dramatic. Where previously a single heavy storm would bring the stream rushing down, full of sediment, only to dry up again in a few days, we now have to wait through two weeks of rain at the beginning of the monsoon before the stream starts to flow. When it does begin to flow it no longer carries the sand and silt that it once did, and when the rains finish, the stream continues to flow for more than a month as the water slowly seeps through the soil and underlying rock.